Eating meat comes with an enormous environmental footprint, with food systems responsible for an estimated 34 per cent of global emissions. And yet, in most countries, meat consumption is continuing to rise.

Our new study investigated whether meat consumption increases as income increases. We specifically tested if there’s a point at which improvements in GDP per capita are no longer associated with greater meat consumption. In other words, in a world of increasing GDP, when might meat consumption peak?

After analysing data for 35 countries, we identified such a tipping point at around US$40,000 (A$57,000) of GDP per capita. Only six of the 35 countries, however, had reached this, with other countries continuing on an increasing trajectory.

Overall, we found each person worldwide ate, on average, 4.5kg more meat per year in 2019 than in 2000. While we can’t say what’s behind the general choice to eat more meat, our study identifies some insightful trends.

The problem with meat

Emissions from meat production are largely due to land clearing, including deforestation, to create more pasture and grow feed for livestock.

To put it into perspective, human settlements occupy only 1 per cent of the planet’s landmass, while livestock grazing and feed production use 27 per cent. Compare this to 7 per cent used for crop production for direct human consumption, and 26 per cent occupied by forests.

As a result, a recent UK study found a vegetarian diet produces 59 per cent fewer emissions than a non-vegetarian one. And interestingly, it found that the average diet for men in the UK had 41 per cent more emissions than that of women, because of their greater intake of meat and other animal-based products.

Despite the growing evidence and awareness of the climate impact of our diets, we found the average amount of meat – beef, poultry, pork and sheep – a person ate each year increased from 29.5kg in 2000 to 34kg in 2019.

Poultry is the most popular option (14.7kg), followed by pork (11.1kg) and beef (6.4kg).

Poultry on the rise

Nearly all countries studied (30 of 35) experienced a steady increase in annual per capita poultry consumption between 2000 and 2019. It doubled in 13 countries, with more than 20kg eaten each year in Peru, Russia and Malaysia.

In addition to the poultry industry’s long-term focus on creating cheap and convenient food, many western consumers are now replacing beef with poultry. One possible reason is because of its smaller environmental footprint: chickens require less land and generate much lower emissions than cattle.

However, this comes at a price. It exposes the world, including Australia, to new virus outbreaks such as the bird flu, and results in the overuse of antibiotics in farm animals. This could lead to antimicrobial resistance developing, and the loss of antibiotics to treat human bacterial infections.

Industrial farming practices have added further pressures, with animals raised in confined spaces where they’re easily exposed to pathogens, viruses and stress, making them more prone to disease.

We have seen similar impacts in China, the world’s largest producer and consumer of pork. Our analysis revealed major dietary fluctuations, such as when pork consumption dropped substantially in 2007 after prices increased by over 50 per cent, following outbreaks of swine influenza and Sars outbreaks in humans at the time.

Which countries have reached peak meat?

While meat consumption increased around the world on average, taking a closer look at individual countries reveals a more complicated story.

Of the 35 countries we studied, 26 had a clear correlation between GDP growth and meat consumption levels. For the remaining nine, there was no such a correlation, while six appeared to have reached a meat consumption peak: New Zealand, Canada, Switzerland, Paraguay, Nigeria and Ethiopia. The reasons for this span both sides of the economic wealth spectrum.

The three western countries may have reduced meat consumption because of conscious preferences for plant-based foods, as the health and environmental benefits become more well known. Most notably, people in New Zealand decreased their average consumption from 86.7kg in 2000 to 75.2kg in 2019.

For the remaining three countries, reaching the peak probably wasn’t voluntary, but related to economic downturn, weather calamities and virus outbreaks. In Paraguay, for example, an outbreak of foot and mouth disease in 2011 resulted in cattle slaughter.

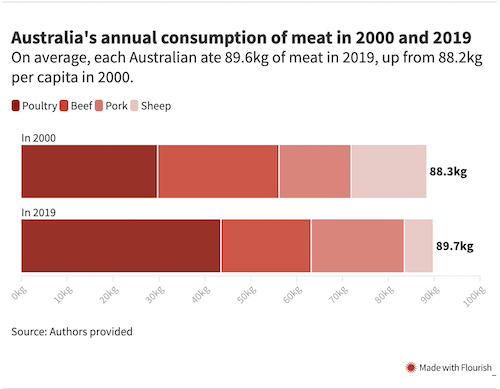

Australia continues to be one of the world’s top meat-eating countries, with an annual consumption of 89.6kg per capita in 2019, up from 88.2kg per capita in 2000. Most of this was poultry.

Outdoor livestock are extremely vulnerable to extreme weather events, such as droughts, heat waves and floods. This is one reason the share of beef in Australia’s meat exports decreased by 15 per cent, due to weather extremes and drought during 2019. Beef consumption in Australia still remains high in relative terms.

Meat was left out of climate talks

Meat consumption was largely left out of the debates at the international climate change summit in Glasgow, Scotland, last month. Our study makes it clear this omission is unacceptable.

The food we eat is a personal choice, but it needs to be an informed personal choice. The climate, environmental and health and welfare implications of our food choices require awareness and role set not only by climate warriors such as activist Greta Thunberg but also by policy leaders.

There were two positive developments at the climate summit: the agreement to put a stop to deforestation (which was joined by Australia) and the collective pledges to reduce the levels of methane (which Australia did not join).

The relationships between deforestation and livestock, and between methane emissions and livestock, must be made transparent. Otherwise, it will be difficult to expect people to shift their food preferences towards more plant-based meals.

The change could start with what we put on our plates this holiday season.

About the authors: Diana Bogueva is Team Manager/ Adjunct Postdoctoral Fellow at University of Sydney; Clare Whitton, Curtin University; Clive Phillips, Former Foundation Professor of Animal Welfare, University of Queensland, Curtin University, and Dora Marinova, Professor of Sustainability, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.