Heat pumps are becoming all the rage around a world that has to slash carbon emissions rapidly while cutting energy costs. In buildings, they replace space heating and water heating – and provide cooling as a bonus.

A heat pump extracts heat from outside, concentrates it (using an electric compressor) to raise the temperature, and pumps the heat to where it is needed. Indeed, millions of Australian homes already have heat pumps in the form of refrigerators and reverse-cycle air conditioners bought for cooling. They can heat as well, and save a lot of money compared with other forms of heating!

Even before the restrictions on Russian gas supply, many European countries were rolling out heat pumps – even in cold climates. Now, government policies are accelerating change. The US, which has had very cheap gas in recent years, has joined the rush: President Joe Biden has declared heat pumps are “essential to the national defence” and ordered production be ramped up.

The ACT government is encouraging the electrification of buildings using heat pumps and is considering legislation to mandate this in new housing developments. The Victorian government recently launched a Gas Substitution Roadmap and is reframing its incentive programs towards heat pumps. Other states and territories are also reviewing policies.

Just how big are the energy cost savings?

Relative to an electric fan heater or traditional electric hot water service, I calculate a heat pump can save 60-85 per cent on energy costs, which is a similar range to ACT government estimates.

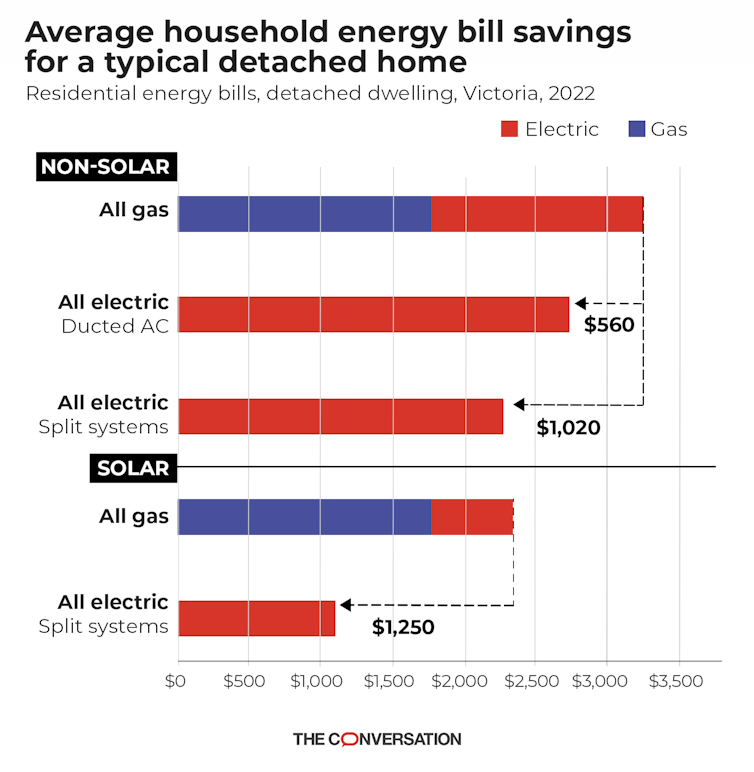

Comparisons with gas are tricky, as efficiencies and energy prices vary a lot. Typically, though, a heat pump costs around half as much for heating as gas. If, instead of exporting your excess rooftop solar output, you use it to run a heat pump, I calculate it will be up to 90 per cent cheaper than gas.

Heat pumps are also good for the climate. My calculations show a typical heat pump using average Australian electricity from the grid will cut emissions by about a quarter relative to gas, and three-quarters relative to an electric fan or panel heater.

If a high-efficiency heat pump replaces inefficient gas heating or runs mainly on solar, reductions can be much bigger. The gap is widening as zero-emission renewable electricity replaces coal and gas generation, and heat pumps become even more efficient.

How do heat pumps work?

Heat pumps available today achieve 300-600 per cent efficiency – that is, for each unit of electricity consumed, they produce three to six units of heat. Heat pumps can operate in freezing conditions too.

How is this possible, when the maximum efficiency of traditional electric and gas heaters is 100 per cent, and cold air is cold?

It’s not magic. Think about your fridge, which is a small heat pump. Inside the fridge is a cold panel called an evaporator. It absorbs heat from the warm food and other sources because heat flows naturally from a warmer object to a cooler object. The electric motor under the fridge drives a compressor that concentrates the heat to a higher temperature, which it dumps into your kitchen. The sides and back of a typical fridge get warm as this happens. So your fridge cools the food while heating the kitchen a bit.

A heat pump obeys the laws of thermodynamics, which allow it to operate at efficiencies from 200 per cent to more than 1000 per cent in theory. But the bigger the temperature difference, the less efficient the heat pump is.

If a heat pump needs to draw heat from the environment, how can it work in cold weather? Remember your fridge keeps the freezer compartment cold while pumping heat into your kitchen. The laws of physics are at play. What we experience as a cold temperature is actually quite hot: it’s all relative.

Outer space is close to a temperature known as absolute zero, zero degrees Kelvin, or –273℃. So a temperature of 0℃ (at which water freezes), or even the recommended freezer temperature of -18℃, is actually quite hot relative to outer space.

The main problem for a heat pump in “cold” weather is that ice can form on its heat exchanger, as water vapour in the air cools and condenses, then freezes. This ice blocks the airflow that normally provides the “hot” air to the heat pump. Heat pumps can be designed to minimise this problem.

How do you choose the right heat pump for your home?

Selecting a suitable heat pump (more commonly known as a reverse-cycle air conditioner) can be tricky, as most advisers are used to discussing gas options. Resources such as yourhome.gov.au, choice.com.au and the popular Facebook page My Efficient Electric Home can help.

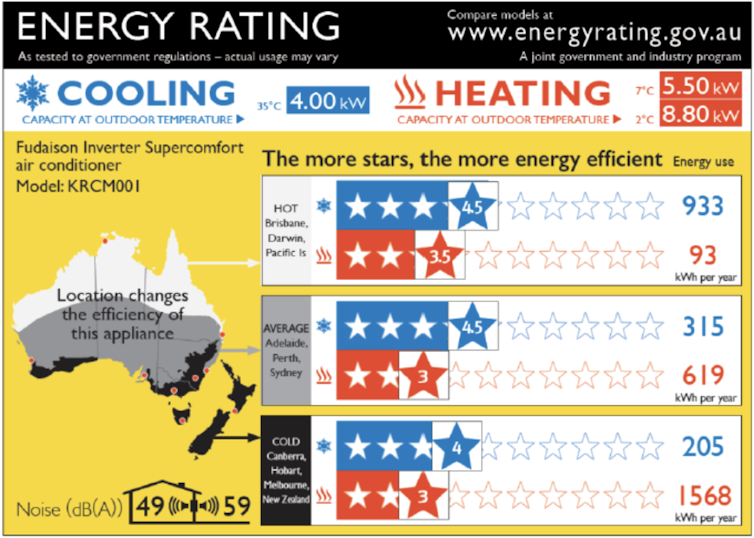

All household units must carry energy labels (see energyrating.gov.au): the more stars the better. The independent FairAir web calculator allows you to estimate heating and cooling requirements of a home and the size needed to maintain comfort.

Bigger heat pumps are more expensive, so unnecessary oversizing can cost a lot more. Also, insulating, sealing drafts and other building efficiency measures allow you to buy a smaller, cheaper heat pump that will use even less energy and provide better comfort.

When using a heat pump, it is very important to clean its filter every few months. A blocked filter reduces efficiency and the heating and cooling output. If you have an older heat pump that no longer delivers as much heat (or cooling), it may have lost some refrigerant and need a top-up.

About the author: Alan Pears is senior industry fellow at RMIT University

This article on focused on the effect of heat pumps on energy costs is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Further reading: Temperature-adapting glass from Singapore could help cut energy costs.