Scientists in Japan have developed a plastic-like material that dissolves in seawater and breaks down in soil – a significant scientific breakthrough at a time when plastic waste continues to accumulate worldwide.

Although many consumers place plastic in recycling bins, only about 9 per cent of it is recycled. According to the World Economic Forum, the equivalent of a dump truck of plastic enters the ocean every minute, and plastic could outnumber fish in the sea by 2050.

Microplastics form when conventional plastics break down into tiny particles. These particles can enter food chains and carry harmful chemicals, posing risks to marine life and human health. Existing biodegradable plastics also rarely break down fully in marine environments or leave behind residues.

Researchers at the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science designed a supramolecular plastic that stays strong during use but dissolves quickly in saltwater.

They built the material using ionic monomers linked by reversible salt bonds, which give it durability in normal conditions while allowing it to dissolve in seawater. More than 90 per cent of the material’s primary component can be recovered and reused after dissolution.

“With this new material, we have created a new family of plastics that are strong, stable, recyclable, can serve multiple functions, and importantly, do not generate microplastics,” said lead researcher Takuzo Aida.

Traditional supramolecular plastics often lack stability because their reversible bonds break down too easily. The researchers addressed this by adding sodium hexametaphosphate, a food additive, and guanidinium-based monomers commonly used in fertilisers. These compounds form stronger cross-linked salt bridges, improving durability without sacrificing degradability.

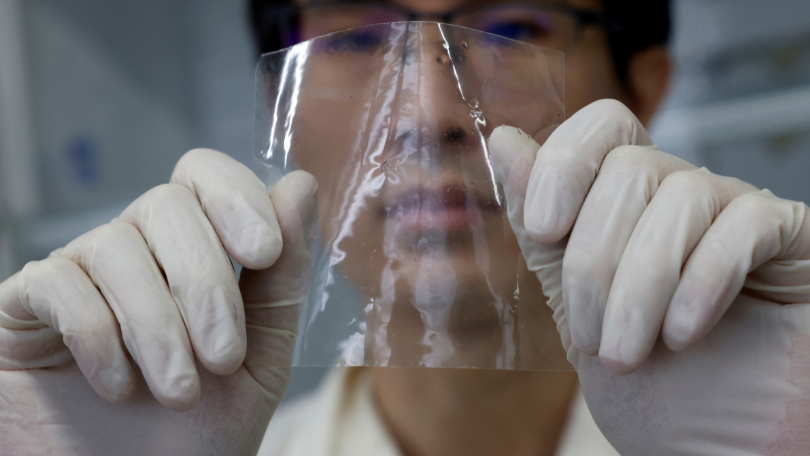

To create the material, the team mixed the compounds in water and isolated the bonded layer, then dried it into a plastic-like sheet. The resulting material can be moulded into different shapes like conventional plastics and coated to make it waterproof. However, once exposed to seawater – especially if scratched – it begins to dissolve.

Laboratory tests showed the plastic starts breaking down within hours in seawater and fully decomposes in soil within about 10 days. As it breaks down, it releases nitrogen and phosphorus, which microbes and plants can absorb.

The researchers say the material could help reduce plastic waste and microplastic pollution, but they will need further development and scaling before commercial use becomes viable.