As New Zealanders plan their summer holiday trips, it’s worth considering different travelling options and their respective cost, both to the budget and the environment.

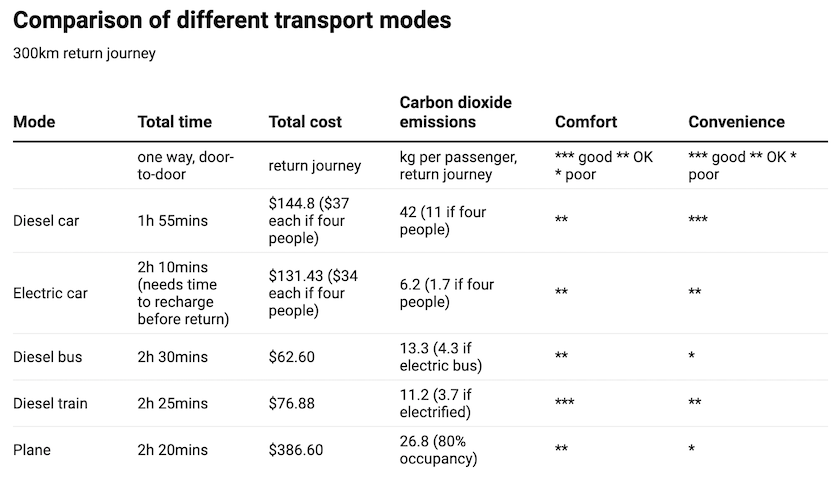

I’ve compared several travel modes (with all assumptions made found here) – a small diesel car, electric car, bus, train or plane – for a door-to-door 300km return journey. The process has identified limitations for each mode, which may help policymakers better understand the challenges involved in developing a low-carbon transport system.

New Zealand’s annual transport emissions have nearly doubled since 1990 and account for more than a fifth of total greenhouse gas emissions.

Emissions from cars, utes and vans have continued to increase even though the NZ Emissions Trading Scheme has been in place for 14 years and has added a “carbon levy” of around 10-15 cents per litre to petrol and diesel.

The Climate Change Commission has recommended the government should:

- Reduce the reliance on cars (or light vehicles) and support people to walk, cycle and use public transport.

- Rapidly adopt electric vehicles.

- Enable local government to play an important role in changing how people travel.

But is it realistic to expect governments to change how people travel? Providing information is perhaps the key.

Transport comparisons

A person’s choice of transport mode is based on a mixture of cost, comfort and convenience as well as speed and safety. But most New Zealanders choose their car out of habit rather than from any analytical reasoning.

Carbon dioxide emissions are rarely a factor in their choice. Although more people now agree that climate change is a major issue, few have been willing or able to take steps to significantly reduce their transport-related carbon footprint.

This analysis is based on my personal experiences travelling between my house on the outskirts of the city of Palmerston North to attend a meeting in the centre of Wellington. It relates to any other similar journey with a choice of transport modes, although the details will vary depending on the specific circumstances.

I compared a 1500cc diesel car I owned for ten years with an electric car which has a 220km range and is mainly charged at home, using rooftop solar. The airport is 8km away from the house, the railway station 7km and the bus station 5km. I included “first and last mile” options when comparing total journey time, cost, carbon emissions, comfort and convenience.

Things to consider before a trip

Travelling by car for one person is relatively costly but has good door-to-door convenience and can be quicker than the bus, train or plane, except during times of traffic congestion. Comfort is reasonable but the driver cannot read, work or relax as they can on a train.

Car drivers usually consider the cost of fuel when planning a journey, but few consider the costs of depreciation, tyre wear, repairs and maintenance as included here. Should more than one person travel in the car, the costs and carbon emissions will be lower per passenger.

Taking a short-haul flight over this distance is relatively costly and the journey is no quicker since there is considerable inconvenience getting to and from the airports. The carbon dioxide emissions per passenger can be lower than for a diesel car (with just the driver), assuming the plane has around 80% occupancy.

For one person, taking a bus or train can be significantly cheaper than taking a car and also offers lower emissions. However, the longer overall journey time and the hassles getting to and from the stations are deterrents. Infrequent bus and train services, often at inconvenient times, can also be disincentives to choosing these modes.

Going electric

The electric car has low carbon emissions, especially if charged from a domestic solar system. Coupled with reasonable comfort and convenience and the lowest journey cost per person when carrying two or more passengers, this supports the government’s policy to encourage the deployment of EVs.

Travelling by train is perhaps the best option overall for one person making this journey. The total cost is less than half that of taking a car. Emissions are around a third of the diesel car. Comfort is good, with the opportunity to work or relax.

Making the whole journey more convenient will help encourage more people to travel by train and help reduce transport emissions. But this will require national and local governments to:

- Encourage Kiwirail to provide more frequent services.

- Electrify all lines.

- Provide cheap and efficient “first-and-last-mile” services to railway stations.

- Undertake a major education campaign to illustrate the full cost, carbon emissions and convenience benefits resulting from leaving the car at home.

About the author: Ralph Sims is Emeritus Professor, Energy and Climate Mitigation at Massey University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.